‘He’s traditional medicine, I’m very alternative’: the unlikely pair on a mental health mission

By Susan Horsburgh

Source: Sydney Morning Herald

March 12, 2021

After psychiatrist and former Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry, 68, met philanthropist Suparna Bhasin, 49, he embraced her case for exploring meditation and breathwork in treatments. He won’t, however, eat broccoli.

PATRICK: I was introduced to Suparna in 2018 at the Melbourne premiere of a documentary about depression called Happy Sad Man. Suparna disclosed that her life had been turned upside down by episodes of bipolar illness, which hadn’t been treated well. That’s what I’ve been working on, so we hit it off straight away in terms of a common purpose. She was incredibly warm, engaging and very unfiltered; she just said exactly what she thought. She had this passion to change things and that American confidence that gets things done.

I didn’t know about her family’s charitable foundation, but I’m always interested in meeting people with lived experience who want to help. She’s recovered from a potentially devastating illness, consciously taken control of her life and wants to improve the situation for other people. She was looking at alternative, complementary therapies and healthy lifestyle changes, like getting enough sleep, not drinking alcohol, a vegetarian diet. At Orygen [the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health, where McGorry is executive director], we’re interested in all those things, too.

The only thing is, because she’s so passionate about meditation and breathing, we have to be careful. In psychiatry, people have made a lot of mistakes and done things that haven’t worked, so we’re committed to making sure what we support is effective. I was worried that might lead to tension, but she sees it as an advantage because we’ll actually do [the research] properly. She’s supporting one of my researchers in establishing a new approach to bipolar at Orygen and also exploring the SKY [Sudarshan Kriya Yoga] breathing technique.

Mental health is seriously underfunded, so I’d been trying for years to get Australians for Mental Health set up as a grassroots social movement. Suparna helped fund it and came on to the board for a while as chair.

There’s an international version called United for Global Mental Health, so we went to the first meeting in scary Johannesburg, wandering the streets with [people carrying] machine guns. Suparna was fine in that environment and also networking, identifying who was important to build relationships with.

Suparna’s not just giving us money; it feels like we’re on a mission. It sounds grandiose, but she’s someone who wants to change the world and she’s impatient to do it. I live a pretty normal life in the suburbs; I don’t mix with high-net-worth individuals, so it’s unlikely we’d have become friends without this connection. I’m always very respectful; I just follow her lead in terms of what she’d like to work on with us.

What annoys me? Her trying to make me eat vegetables, perhaps. I couldn’t live her lifestyle. I like to have a glass of wine; I have tried to meditate, but I’m too restless. I don’t eat any vegetables if I can help it, and she’s vegetarian, so there’s some gentle ribbing. I think she’s given up, though.

SUPARNA: When we met, I told Pat how I’d had a bad breakdown in my early 20s. I now believe I was misdiagnosed and over-medicated, but at the time I didn’t know what was going on. Now it’s my mission to [promote] the things that have been life-saving for me, like meditation and breathwork. I wish someone had told me about them.

Pat’s one of the kindest, most generous people I know. When we met, he was the founder of Headspace [the flagship mental health service for Australians aged 12 to 25] and he’d still see clients through the public system.

I introduced him recently to somebody with a daughter who’s struggling; she called him for help because she didn’t know where else to go. He called her back within five minutes – and has checked up on her five times since then. I’ve heard that story more than once.

At his level, to be as humble and caring as he is, it led me, as a funder, to say, “Whatever this man wants, I want to see how I can get it for him.” He’s dedicated his whole life to a population that’s stigmatised, that many people don’t understand and don’t care to understand. Helping vulnerable young people that are suffering – that’s his sole driver. It’s not money, fame or recognition.

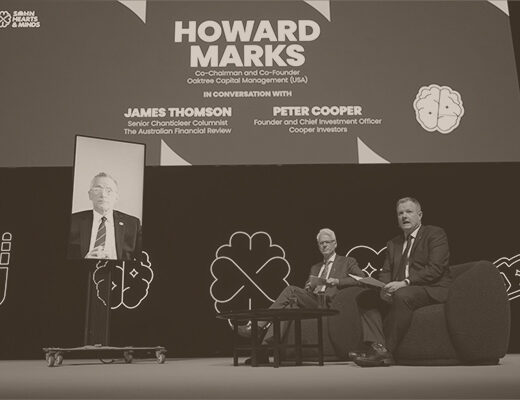

My fiancé Peter Cooper’s investment management business, Cooper Investors, gives $1 million a year to mental-health medical research, so that’s funding the Orygen study on SKY breathing. [The technique] strips away stress in the nervous system, removing impressions in the mind of trauma, regret, anxiety and depression.

We did a course [with Orygen staff] and, in the final session, Pat said, “I did it because Suparna asked me to.” I just wept; I felt that was friendship, not because I was writing cheques. I’ve never felt like he’s sucking up to me. People [are fake] all the time, but I’ve felt such sincerity with Pat.

I used to be a life coach and he has shared very vulnerably [his questions] about what should be the next step for him. I said, “Pat, I feel like you’re a global leader now.”

What annoys me is that doctors don’t take good care of themselves. You want the doctors in your life to be the embodiment of health. Pat refuses to eat vegetables. He has personal freedom to choose whatever he wants, but it’s a metaphor for something bigger. And he knows it.

I’m an Indian woman from New York [who moved to Australia in 2015]; he’s an Irish-born psychiatrist. He’s traditional medicine and therapies; I’m very alternative. We’re quite an unlikely pair in that way, but we have a shared interest in humanity. I know there’s a place for medicine and Pat knows there’s a place for meditation and that’s what’s keeping us together – that desire to keep ticking all the boxes.