Each year we provide a book to our investors with the important lessons we have drawn from it and its linkage to our process.

“Over the past 10 years, in order to achieve the growth, development and scale necessary to go from less than 1,000 stores to 13,000 stores and beyond, we have had to make a series of decisions that, in retrospect, have led to the watering down of the Starbucks Experience, and what some might call the commodisation of our brand.

Many of these decisions were probably right at the time, and on their own merit would not have created the dilution of the experience; but in this case, the sum is much greater and, unfortunately, much more damaging than the individual pieces.”

Hendrik Bessembinder studied shareholder wealth creation of US companies from 1950 to 2020. He observed the most successful group (the top 100 wealth creators) experienced material share price drawdowns during the decade they were most successful – the average drawdown was 32.5%. That is, on their way to creating great wealth, they suffered a great fall.

We describe these falls as Hubris-to-Humility cycles: success can lead “people [to] become arrogant, regarding success virtually as an entitlement, and they lose sight of the true underlying factors that created success in the first place”.

Whilst these events can be painful the humility phase can be a powerful de-risking event for investors. A crisis can provide the focus and urgency needed for businesses to correct mistakes and refocus on the core, which reduces operational risk. And so, in the right circumstances, the risk-adjusted value of the business can be rising at a time when disgruntled investors are selling and the share price is falling.

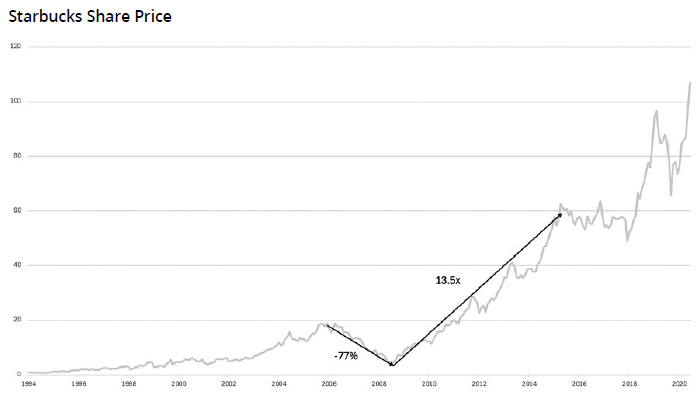

Starbucks (SBUX) experienced a Hubris-to-Humility cycle in the late noughties. Starbucks had for most of its history enjoyed incredible success. But that success bred hubris, they drifted away from their core and diluted their customer proposition. Then the GFC hit. Starbucks share price declined by 77%.

Onward is the story of Starbucks’ Hubris-to-Humility cycle during this period and Howard Schultz’s leadership.

These are our lessons from the book.

Provide a positive and optimistic vision of the future: a humility cycle creates fear and anxiety for the future – will the company survive? Will I still have a job? Howard recognised this and did not “cast blame for the mistakes” and sought to provide a positive vision for the future. Howard also struck an important balance with the past – he recognised the important lessons of Starbucks’ history but was not nostalgic, recognising they must reinvent themselves to succeed.

Talent refresh: A fellow CEO told Howard that “most of your top leaders will be gone or new within a year”. The critical phase of a turnaround requires people that are “all-in”. Many of the people in senior leadership will be part of the “complacent class” unable to make this switch. Howard was willing to make the hard decisions and remove “good people” who had the wrong culture and drive.

There are no silver bullets: “I could not help but hope that there just might be one thing that would miraculously solve all our problems”. Howard continually sought a “silver bullet”, these included new drink categories and technology innovations. None of these delivered the expected outcomes. But they did divert focus and their failure partially undermined Howard’s leadership. Howard finally concluded success would only be achieved by focusing, relentlessly on the core.

Focus on re-energising the customer proposition, not short-term financial metrics: Schultz recounts some advice he was offered “if you reduce the quality just 5 percent, no one would know, and that’s a few million dollars right there”. But Schultz remarks “at these recommendations and others, I did not blink”. He focused on the core drivers of long-term value – “One cup. One customer. One partner. One experience at a time. We had to get back to what mattered most”.

There will be low-hanging fruit to improve the operations: “growth and success can cover up a lot of mistakes”. Starbucks’ success had allowed inefficient practices to creep in and fester, there was never any serious management focus on cutting them out. This included outdated technology, haphazard inventory management, dirty stores, excess wastage and poor labour scheduling. But the humility cycle forced a first-principle review of operations with the urgency to change.

Focus on customer observations: there was so much negativity toward Starbucks from journalists and Wall Street and recent financial performance was bleak. Many questioned the viability of the model. But beneath this negativity there were strong signals available to the observational investor. Starbucks shuttered hundreds of poor performing stores – this led to a huge outpouring from effected customers (including “Save Our Starbucks”). This highlighted the strong customer proposition and unique place Starbucks served in communities i.e. would a fast-food restaurant elicit a similar response?

Source: Factset, Cooper Investors Analysis

Starbucks’ share price increased by 13.5x in the proceeding 8 years.

Today Starbucks is once again suffering a Hubris-to-Humility cycle. Whilst the circumstances and drivers are different compared to the Onward era, the above lessons are enduring.